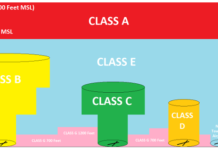

Airspace was divided up for the safety of pilots and planes in 1993. Based on the type and amount of traffic, the FAA created the Classes we use today around the ICAO descriptions. Ranging from A-E and G each airspace has its own rules and regulations that a pilot must comply to.

The classes span the most restrictive, Class A, to the least restrictive, Class G. Let’s explore Class A a little further.

Identifying

Probably the easiest thing about Class A airspace is identifying it. Now, that’s not to say that it’s shown anywhere on any map though. The airspace is across all the continental US and Alaska, stretching out over the coastal waters by 12 nautical miles. It starts at 18,000 feet mean sea level (MSL) and goes up to and including Flight level (FL) 600 (or 60,000 feet MSL).

But wait, it’s not quite that simple. In the case of Class A airspace, and ONLY Class A airspace, the identifier isn’t based on local barometric pressure. Pilots fly in Class A using the “Standard Datum Plane”. We will get more into this a little later, but for the purposes of identifying Class A a pilot enters 29.92 in Hg into their Kollsman Window. This means that technically Class A does not start at 18,000 feet MSL exactly, but rather 18,000 feet MSL from a theoretical point near the surface that measures 29.92 inches of Mercury.

However, for any test that you would take from a Private Pilot’s perspective, the boundaries of Class A airspace is 18,000 feet MSL to FL600. An easy way to remember is “Class A – A means Above Everything”. Jets and larger, faster airplanes fly these altitudes to be above the weather. The airspace is the fast lane of the sky.

Why use the Standard Datum Plane?

To understand this, we need to first understand what a flight level is. Flight levels are altitudes set at standard pressure. For example: Flight level 230 (FL230) is 23,000 feet MSL based on the standard theoretical pressure of 29.92 in Hg.

Now, imagine this if you will. You are flying along on a cross country in your Cessna 172. You go from one location where the local pressure is 30.02 and you travel to your destination where the local pressure is 28.78. The scenario is, you don’t update your barometer. What happens?

Remember from one of my previous posts how to calculate pressure altitude? Pressure Altitude is (Standard Pressure – Local Pressure) x 1000 + Elevation.

So if you are flying at 3,000 feet on your altitude indicator and set 30.02 pressure you have 100 feet that you “add” by setting your pressure correctly. However, if you don’t change your pressure guage and fly into your destination at 28.78 you may find yourself 1,000 feet lower than you expected. My private instructor used to say “When flying high to low look out below”! He’d be so proud that I remembered that.

For this reason, Class A uses the standard pressure so ALL airplanes are on the same pressure and therefore no matter what the local pressure is all the planes in the air follow altitude together.

Regulations

Almost everything related to flying has regulations and airspace is no exception. But where do you go to find the regs? None other than the FAA. The FAR (federal aviation regulation) is the collection of all aviation regulations and can be found in Title 14 under the Code of Federal Regulations.

Airspace rules are under Part 91 of the FARs and Class A specifically under 91.135.

The few key points from the regs are:

- “…each person operating an aircraft in Class A airspace must conduct that operation under instrument flight rules…”

- Clearance is required prior to entering the airspace

- Two-way radio is required on frequency assigned by ATC

- Transponder is required

- Required equipment for operating in Class A can be found in 91.215 and 91.225 after Jan 1, 2020.

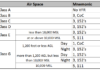

Weather Minimums

Class A airspace is for IFR flight or Instrument Flight Rules. As such there are no weather minimums listed for this airspace. All flights are under ATC control and flying on Instruments.

Emergencies

What happens if you are flying in Class A and have a radio failure? Can you continue flight under VFR conditions?

If you read this blog post on AVWeb.com they provide a very convincing argument on why you may fly VFR in Class A airspace. The basic gist of the argument is if you lose communications with ATC while in Class A airspace you have two options. 1) Continue the flight as planned/expected. 2) Operate under VFR rules to the nearest safe airport and land under VFR rules.

If you continued your flight as planned/expected then ATC would be extra busy routing planes around you since you can’t communicate with them. While technically legal, depending on where you lost communications you may have some very upset controllers.

If, however, you fly your flight under VFR in Class A, while squaking 7600, and proceed to the nearest, safest airport you can land under VFR rules. This accomplishes two things: 1) you can fix your plane and 2) You do your part to help keep the skies as safe as possible. You may also make friends with controllers who don’t have to reroute other planes to watch out for you.

How can this VFR in Class A be legal? By following this simple reg 91.185 IFR operations: Two-way communication failure. If you follow this reg IN ORDER of the provisions you get the following:

A) Unless authorized pilots with radio failure will follow the rules of this section

B) VFR (note, this section comes first, which would mean that you should follow it first). “If the failure occurs in VFR conditions, or if VFR conditions are encountered after the failure, each pilot shall continue the flight under VFR and land as soon as practicable”.

C) IFR. This is where you get the instructions to follow what you were given/filed etc to complete your flight.

If you are going to fly in any airspace you should know what the rules and regs say should things go wrong. Be proactive in your quest for knowledge on when an exception to the rules applies.

Exceptions

As with all rules there are a few exceptions to the rules. The FAA has given themselves some space here by always adding the statement “Unless authorized by ATC” in almost all the regs. This means that there are times where ATC can authorize a diversion from the regs for anyone, for any reason. However, don’t expect that just because you ask for it.

Another exception is for gliders and sail planes. ATC will issue them a special clearance to fly in Class A if they are flying the mountains and more likely to bust Class A airspace. There are also some high-altitude skydiving operations that may pass through Class A. For these exceptions you must submit your request, in writing, to the appropriate controlling ATC facility no less than 4 days in advance.

Conclusion

Class A airspace is simple if you understand the very basic rules, clearance to enter, IFR operations unless authorized, and starting at 18,000 feet MSL. All other changes are special cases that unless specifically stated on an FAA test will not factor in.

For more information on other airspaces Check out my overview of Airspace.

What have you experienced in Class A airspace? Have you been a pilot of a plane that has experienced a deviation to the standard airspace rules? Let me know in the comments.